88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Brigitte Bardot | |

|---|---|

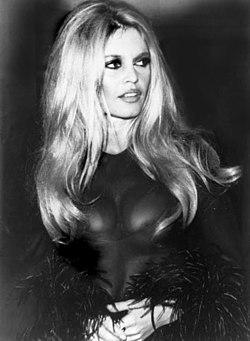

Bardot in 1962 | |

| Born | Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot 28 September 1934 Paris, France |

| Died | 28 December 2025 (aged 91) Saint-Tropez, France |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active |

|

| Works | Filmography |

| Spouses | Bernard d'Ormale (m. 1992) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Mijanou Bardot (sister) |

| Signature | |

Brigitte Bardot (born September 28, 1934, Paris, France—died December 28, 2025, Saint-Tropez, France) was a French film actress and singer who became an international sex symbol in the 1950s and ’60s. She later stepped away from stardom and gained recognition as a champion of animal rights.

Film career

Bardot was born to wealthy bourgeois parents, and at the age of 15 she posed for the cover of Elle (May 8, 1950), France’s leading women’s magazine. Roger Vadim, an aspiring director, was impressed and shrewdly fashioned her public and screen image as an erotic child of nature—blond, sensuous, and amoral. In two motion pictures directed by Vadim—Et Dieu créa la femme (1956; And God Created Woman) and Les Bijoutiers du claire de lune (1958; “The Jewelers of Moonlight”; Eng. title The Night Heaven Fell)—Bardot broke contemporary film taboos against nudity and set box-office records in Europe and the United States. (Bardot was married to Vadim from 1952 to 1957.)

Bardot was the darling of disaffected French leftists, to whom she symbolized an artless disregard for conventional morality. Of her many films the most notable are Vie privée (1962; “The Private Life,” A Very Private Affair), Le Mépris (1963; Contempt), Viva Maria! (1965), Dear Brigitte (1965), and Masculin-Féminin (1966; Masculine Feminine). Bardot appeared in her final films in 1973 and subsequently retired.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot (French: [bʁiʒit anmaʁi baʁdo]; 28 September 1934 – 28 December 2025), often referred to by her initials B.B.,[1][2] was a French actress, singer, model, and animal rights activist. She became one of the best-known symbols of the sexual revolution and gained international fame for portraying characters associated with hedonistic lifestyles. Although she withdrew from the entertainment industry in 1973, she remained a major pop culture icon.[3][4] She appeared in 47 films, performed in several musicals, and recorded more than 60 songs. She was awarded the Legion of Honour in 1985.

Born and raised in Paris, Bardot was an aspiring ballerina during her childhood. She began her acting career in 1952 and achieved international recognition in 1957 for her role in And God Created Woman (1956), catching the attention of many French intellectuals and earning her the nickname "sex kitten".[5] She was the subject of philosopher Simone de Beauvoir's 1959 essay The Lolita Syndrome, which described her as a "locomotive of women's history" and built upon existentialist themes to declare her the most liberated woman of France. She won a 1961 David di Donatello Best Foreign Actress Award for her work in The Truth (1960). Bardot later starred in Jean-Luc Godard's film Le Mépris (1963). For her role in Louis Malle's film Viva Maria! (1965), she was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress. French president Charles de Gaulle called Bardot "the French export as important as Renault cars".[6]

After retiring from acting in 1973, Bardot became an animal rights activist and created the Brigitte Bardot Foundation. She was known for her strong personality, outspokenness, speeches on animal welfare, and for her long-term support of far-right views. She was fined twice for public insults, and five times for inciting racial hatred[7][8] for her criticism of Muslims in France and calling residents of Réunion "savages". She responded: "I never knowingly wanted to hurt anybody. It is not in my character [...] Among Muslims, I think there are some who are very good and some hoodlums, like everywhere."[9][10] Bardot was a member of the Global 500 Roll of Honour of the United Nations Environment Programme and received several awards and accolades from UNESCO and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA).

Early life

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born on September 28, 1934 in the 15th arrondissement of Paris to Louis Bardot (1896–1975) and Anne-Marie Mucel (1912–1978).[11] Bardot's father, who originated from Ligny-en-Barrois, was an engineer and the proprietor of several industrial factories in Paris.[12][13] Her mother was the daughter of an insurance company director.[14] She grew up in a conservative Catholic family, as had her father.[15][10] She suffered from amblyopia as a child, which resulted in decreased vision of her left eye.[16] She had one younger sister, Mijanou Bardot.[17]

Bardot's childhood was prosperous; she lived in her family's nine-bedroom apartment at 1 Rue de la Pompe,[18] in the luxurious 16th arrondissement;[19][20] however, she recalled feeling resentful in her early years.[21] Her father demanded that she follow strict behavioral standards, including good table manners, and wear appropriate clothes.[22] Her mother was highly selective in choosing companions for her, so Bardot had very few childhood friends.[23]

During her childhood, she, her sister, and their parents spent weekends on her paternal grandparents' property, at 17 rue du Général Leclerc in Louveciennes, with a chalet imported from Norway for Exposition Universelle (1889) and large gardens,[18][24] where she later celebrated her marriage to Jacques Charrier.[25]

Bardot recalled a personal traumatic incident when she and her sister broke their parents' favourite vase while they were playing in the house. The sisters' father whipped both of them 20 times and subsequently treated the two like "strangers", demanding that they address their parents by the formal second-person pronoun vous, used in French when speaking to unfamiliar or higher-status persons outside the immediate family.[26] The incident led to Bardot decisively resenting her parents and to her future rebellious lifestyle.[27]

During World War II, when Paris was occupied by Nazi Germany, Bardot spent more time at home due to increasingly strict civilian surveillance.[20] She became engrossed in dancing to records, which her mother saw as a potential for a ballet career.[20] Bardot was admitted at the age of seven to the private school Cours Hattemer.[28] She went to school three days a week, which gave her ample time to take dance lessons at a local studio under her mother's arrangements.[23] In 1949, Bardot was accepted at the Conservatoire de Paris. She attended ballet classes held by Russian choreographer Boris Knyazev for three years.[29] She also studied at the Institut de la Tour, a private Catholic high school near her home.[30]

Career

Beginnings: 1949–1955

Hélène Gordon-Lazareff, the director of the magazines Elle and Le Jardin des Modes, hired Bardot in 1949 as a "junior" fashion model.[31] On 8 March 1950, 15-year-old Bardot appeared on the cover of Elle, which brought her an acting offer for the film Les Lauriers sont coupés from director Marc Allégret.[32][33] Her parents opposed her becoming an actress, but her grandfather was supportive, saying that "If this little girl is to become a whore, cinema will not be the cause."[A]

At the audition, Bardot met Roger Vadim, who later notified her that she did not get the role.[35] They subsequently fell in love.[36] Her parents fiercely opposed their relationship; her father announced to her one evening that she would continue her education in England and that he had bought her a train ticket for the following day.[37] Bardot reacted by putting her head into an oven with open fire; her parents stopped her and ultimately accepted the relationship, on condition that she marry Vadim at the age of 18.[38]

When Bardot was 15 years old,[39] she began modeling.[40][41] She appeared on the cover of Elle in 1950 and 1952, which both brought acting roles,[41] the first, released in 1952, a small part in the comedy film Crazy for Love, directed by Jean Boyer and starring Bourvil.[42] She was paid 200,000 francs (about US$575 in 1952[43]) for the small role portraying a cousin of the main character.[42] Bardot had her second film role in Manina, the Girl in the Bikini (1952), directed by Willy Rozier.[44] She also had roles in the 1953 films, The Long Teeth and His Father's Portrait. Bardot had a small role in a Hollywood-financed film being shot in Paris in 1953, Act of Love, starring Kirk Douglas. She received media attention when she attended the Cannes Film Festival in April 1953.[45]

Bardot had a leading role in 1954 in an Italian melodrama, Concert of Intrigue, and in a French adventure film, Caroline and the Rebels. She had a good part as a flirtatious student in 1955's School for Love, opposite Jean Marais, for director Marc Allégret. Bardot played her first sizable English-language role in 1955 in Doctor at Sea as the love interest of Dirk Bogarde. The film was the third most popular movie in Britain that year.[46] Bardot had a small role in The Grand Maneuver (1955) for director René Clair, supporting Gérard Philipe and Michèle Morgan. Her part was bigger in The Light Across the Street (1956) for director Georges Lacombe. She had another in the Hollywood film Helen of Troy, playing Helen's handmaiden. For the Italian movie Nero's Weekend (1956), brunette Bardot was asked by the director to appear as a blonde. She dyed her hair rather than wear a wig; she was so pleased with the results that she decided to retain the color.[47]

Rise to stardom: 1956–1962

Bardot then appeared in four movies that made her a star. First was a musical, Naughty Girl (1956), where Bardot played a troublesome school girl. Directed by Michel Boisrond and co-written by Roger Vadim, it was also the first time Bardot appeared alongside Alain Delon in a sketch film where they shared a segment. The film was a major success and became the 12th most popular film of the year in France.[48][49]

It was followed by a comedy, Plucking the Daisy (1956), also written by Vadim. This was succeeded by The Bride Is Much Too Beautiful (1956) with Louis Jourdan. Finally, there was the melodrama And God Created Woman (1956). The movie marks Vadim's debut as director, with Bardot starring opposite Jean-Louis Trintignant and Curt Jurgens. The film, about an immoral teenager in an otherwise respectable small-town setting, was an even larger success, not just in France but also around the world, listed among the ten most popular films in Great Britain in 1957.[50]

In the United States, the film was the highest-grossing foreign film ever released, by grossing $12 million (earning $4 million), which author Peter Lev describes as "an astonishing amount for a foreign film at that time".[51][52]It turned Bardot into an international star.[45] From at least 1956,[53] she was hailed as the "sex kitten".[54][55][56] The film scandalized the United States and some theater managers were even arrested just for screening it.[6] Paul O'Neil of Life (June 1958) in describing Bardot's international popularity, writes:

During her early career, professional photographer Sam Lévin's photos contributed to the image of Bardot's sensuality. British photographer Cornel Lucas made images of Bardot in the 1950s and 1960s that have become representative of her public persona. Bardot followed And God Created Woman up with La Parisienne (1957), a comedy co-starring Charles Boyer for director Boisrond. She was reunited with Vadim in another melodrama The Night Heaven Fell (1958), and played a criminal who seduced Jean Gabin in In Case of Adversity (1958). The latter was the 13th most seen movie of the year in France.[58] In 1958, Bardot became the highest-paid actress in the country of France.[59] She was voted among the top ten box office draws in North America based solely on her French films, something that had never happened before.[49] In August 1956 it was announced Preston Sturges would direct her in Long Live the King but the film was never made.[60]

The Female (1959) for director Julien Duvivier was popular, but Babette Goes to War (1959), a comedy set in World War II, was a huge hit, the fourth biggest movie of the year in France.[61] Also widely seen was Come Dance with Me (1959) from Boisrond. Bardot's next film was courtroom drama The Truth (1960), from Henri-Georges Clouzot. It was a highly publicized production, which resulted in Bardot having an affair and attempting suicide. The film was Bardot's biggest commercial success in France, the third biggest hit of the year, and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film.[62] Bardot was awarded a David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actress for her role in the film.[63]

International films and singing career: 1962–1968

Bardot made a comedy with Vadim, Please, Not Now! (1961), and had a role in the all-star anthology, Famous Love Affairs (1962). Bardot starred alongside Marcello Mastroianni in a film inspired by her life in A Very Private Affair (Vie privée, 1962), directed by Louis Malle. More popular than that was her role in Love on a Pillow (1962). In the mid-1960s, Bardot made films that seemed to be more aimed at the international market. She starred in Jean-Luc Godard's film Le Mépris (1963), produced by Joseph E. Levine and starring Jack Palance.[64]

The following year, she co-starred with Anthony Perkins in the comedy Une ravissante idiote (1964). Dear Brigitte (1965), Bardot's first Hollywood film, was a comedy starring James Stewart as an academic whose son develops a crush on Bardot. Bardot's appearance was relatively brief in the film, and the movie was not a big success. More successful was the Western buddy comedy Viva Maria! (1965) for director Louis Malle, appearing opposite Jeanne Moreau. It was a big hit in France and many other countries but not in the United States as much as had been hoped.[64]

After a cameo appearance in Godard's Masculin Féminin (1966), Bardot starred in her first outright flop in some years, Two Weeks in September (1968), a French–English co-production.[65] She had a small role in the all-star Spirits of the Dead (1968), acting opposite Alain Delon, then tried a Hollywood film again: Shalako (1968), a Western starring Sean Connery, which was another box-office disappointment.[66]

Bardot participated in several musical shows and recorded many popular songs in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly in collaboration with Serge Gainsbourg, Bob Zagury, and Sacha Distel, including "Harley Davidson"; "Je me donne à qui me plaît"; "Bubble gum"; "Contact"; "Je reviendrai toujours vers toi"; "L'Appareil à sous"; "La Madrague"; "On déménage"; "Sidonie"; "Tu veux, ou tu veux pas?"; "Le Soleil de ma vie" (a cover of Stevie Wonder's "You Are the Sunshine of My Life"); and "Je t'aime... moi non plus". Bardot pleaded with Gainsbourg not to release this duet and he complied with her wish; the following year, he rerecorded a version with British-born model and actress Jane Birkin that became a massive hit all over Europe. The version with Bardot was issued in 1986 and became a download hit in 2006 when Universal Music made its back catalog available to purchase online, with this version of the song ranking as the third most popular download.[67]

Final films: 1969–1973

From 1969 to 1972, Bardot was the official face of Marianne, who had previously up until then been anonymous, to represent the liberty of France.[68][69]

Bardot's next film Les Femmes (1969) was a flop, although the screwball comedy The Bear and the Doll (1970) performed better. Her last few films were mostly comedies: Les Novices (1970), Boulevard du Rhum (1971) (with Lino Ventura). The Legend of Frenchie King (1971) was popular, helped by Bardot co-starring with Claudia Cardinale. Bardot made one more movie with Vadim, Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman (1973), in which she played the title role. Regarding the film, Vadim said: "Underneath what people call 'the Bardot myth' was something interesting, even though she was never considered the most professional actress in the world. For a few years, since she has been growing older and the Bardot myth has become just a souvenir, I wanted to work with Brigitte. I was curious in her as a woman, and I had to get to the end of something with her, to get out of her and express many things I felt were in her. Brigitte always gave the impression of sexual freedom – she is a completely open and free person, without any aggression. So I gave her the part of a man – that amused me."[70]

During the filming, Bardot said: "If Don Juan is not my last movie it will be my next to last."[71] She kept her word and made only one more film, The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot (1973). In 1973, Bardot announced she was retiring from acting as "a way to get out elegantly".[72] In 1974, Bardot appeared in a nude photo shoot in Playboy magazine, which celebrated her 40th birthday.[73]

Animal rights activism

Bardot met Paul Watson in 1977, the same year he founded the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, during an operation to condemn the massacre of seal pups and seal hunting on the Canadian ice floe.[74] In support of animal protection, Bardot went to the ice floe after being invited by Watson.[75] Bardot posed lying down next to the seal pups; the photos were seen worldwide. Bardot and Watson remained friends.[76]

After appearing in more than 40 motion pictures and recording several music albums, Bardot used her fame to promote animal rights. In 1986, she established the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the welfare and protection of animals.[77] She became a vegetarian[78] and raised three million francs (about US$430,000 in 1986[43]) to fund the foundation by auctioning off jewelry and personal belongings.[77]

Bardot was a strong animal rights activist and a major opponent of the consumption of horse meat.[79][80] In 1989, while looking after her neighbor Jean-Pierre Manivet's donkey, it displayed excessive interest in Bardot's older donkey mare, and she subsequently had the neighbor's donkey castrated due to concerns the mating would prove fatal for her mare. The neighbor then sued Bardot, and Bardot later won, with the court ordering Manivet to pay 20,000 francs for creating a "false scandal".[81][82] Bardot urged French television viewers to boycott horse meat and was soon the target of death threats in January 1994. Not backing off from the threats, she sent a letter to the minister of agriculture, Jean Puech, calling on him to ban the sale of horse meat.[83] Bardot wrote a 1999 letter to People's Republic of China President Jiang Zemin, published in French magazine VSD, in which she accused the PRC of "torturing bears and killing the world's last tigers and rhinos to make aphrodisiacs". She donated more than US$140,000 over two years in 2001 for a mass neutering and adoption program for Bucharest's stray dogs, estimated to number 300,000.[84]

In August 2010, Bardot addressed a letter to Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, appealing for the sovereign to halt the killing of dolphins in the Faroe Islands. In the letter, Bardot described the activity as a "macabre spectacle" that "is a shame for Denmark and the Faroe Islands ... This is not a hunt but a mass slaughter ... an outmoded tradition that has no acceptable justification in today's world".[85] On 22 April 2011, French culture minister Frédéric Mitterrand officially included bullfighting in the country's cultural heritage. Bardot wrote him a highly critical letter of protest.[86] On 25 May 2011, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society renamed its fast interceptor vessel, MV Gojira, as MV Brigitte Bardot in appreciation of her support.[87]

From 2013, the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, in collaboration with Kagyupa International Monlam Trust of India, operated an annual veterinary care camp. Bardot committed to the cause of animal welfare in Bodhgaya over several years.[88] On 23 July 2015, Bardot condemned Australian politician Greg Hunt's plan to eradicate 2 million cats to save endangered species such as the Warru and night parrot.[89] At the age of 90, Bardot appealed to free activist Paul Watson, who had been detained in Greenland since 21 July 2024, when Japan requested his extradition. Through a request expressed in mid-October 2024 by her lawyers and Sea Shepherd France, Bardot asked French President Emmanuel Macron to grant Watson political asylum. Bardot asked Macron to show "a little bit of courage". During that month, she initiated a demonstration in support of Watson in front of the Hôtel de Ville, Paris.[74] Bardot also wrote a letter to Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, asking her to "not choose the camp of the oceans' gravediggers".[90]

Personal life

Habits

Bardot had a habit of going barefoot in the streets of Saint-Tropez and Capri,[91] which became a part of her public image, and was incorporated into her character Juliette in And God Created Woman.[92]

Relationships and family

Bardot was married four times with her final marriage lasting longer than the previous three combined. By her own count, she had a total of 17 romantic relationships.[93] She often left one partner for another when, in her words, "the present was getting lukewarm"; she explained, "I have always looked for passion. That's why I was often unfaithful. And when the passion was coming to an end, I was packing my suitcase."[94]

Roger Vadim

Bardot married director Roger Vadim on 20 December 1952, at Notre-Dame-de-Grace de Passy,[95] when she was 18.[96] They separated in 1956 after she became involved with And God Created Woman co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant, and they divorced the following year.[45] Trintignant was at the time married to actress Stéphane Audran. Bardot and Vadim had no children together, but remained in contact for the rest of his life and later collaborated on several projects. Bardot and Trintignant lived together for about two years, spanning the period before and after her divorce from Vadim, although they never married. Their relationship was complicated by Trintignant's frequent absences due to military service and Bardot's affair with musician Gilbert Bécaud.[97]

Jacques Charrier

After recovering from an overdose in 1958, Bardot began a relationship with actor Jacques Charrier, whom she married in Louveciennes,[98][99] on 18 June 1959. She had an affair with Glenn Ford in the early 1960s.[100] Bardot and Charrier divorced in 1962.[101] Sami Frey was mentioned as the reason for her divorce from Charrier. Bardot was enamoured of Frey, but he quickly left her.[102]

Pregnancy and son

Bardot became pregnant before she and Charrier married.[97] Bardot was extremely dismayed—she had previously stated "I am not a mother, nor do I want to be one"[103]—and sought an abortion; however, abortion was illegal at that time in France.[104] In her book Initiales B. B: Mémoires, she recalled: "I looked at my flat, slender belly in the mirror like a dear friend upon whom I was about to close a coffin lid."[105] Numerous times, she punched herself in the stomach and asked her doctor for morphine in an attempt to abort the baby.[106]

During the final months of her pregnancy, photographers surrounded her house, vying for photos of a pregnant Bardot.[104] Nicolas-Jacques Charrier was born on 11 January 1960, seven months after their wedding.[101] He was Bardot's only child. She had been so wary of the press that she decided to give birth at home.[104] Following his birth, Bardot became depressed and attempted suicide.[103]

She later wrote that her son was a "cancerous tumour" and that she would have "preferred to give birth to a little dog".[106] She also added, "I'm not made to be a mother. I'm not adult enough—I know it's horrible to have to admit that, but I'm not adult enough to take care of a child."[105] She refused to breastfeed Nicolas and whenever she held him, he sensed her agitation and began to cry.[104]

After she and Charrier divorced, the latter gained sole custody of Nicolas.[107] When Nicolas was 12, he asked Bardot if he could stay with her, but she turned him away in favour of party guests. Nicolas was hurt and did not speak to her afterwards. In her memoirs, Bardot wrote that she loved Nicolas "the most in the world", but Nicolas wanted nothing to do with her.[104] When he married Norwegian model Anne-Line Bjerkan in 1984, Bardot was not invited to the wedding.[104][108]

Bardot became a grandmother when the two had daughters in 1985 and 1990. She tried to make peace with him on multiple occasions, but to no avail.[104] In 1997, Charrier and Nicolas sued her and her publisher, Grasset, for the hurtful remarks she had made in her memoir. She was ordered to pay Charrier £17,000 and Nicolas £11,000.[106] In 2018, she stated that she and Nicolas, by then a grandfather himself,[104] were on good terms, speaking regularly and visiting each other once a year.[107][108]

Gunter Sachs

Bardot's third marriage was to German millionaire playboy Gunter Sachs, lasting from 14 July 1966 to 7 October 1969, though they had separated the previous year.[97][45][109]

Bernard d'Ormale

Bardot's fourth and last husband was Bernard d'Ormale, who has been described as a former advisor to the right-wing politician, Jean Marie Le Pen.[110] They were married from 16 August 1992 until her death on 28 December 2025.[111]

Other relationships

Bardot was invited to the birthday party of musician Sacha Distel in 1958, and they had a much-publicized relationship until 1959.[112] From 1963 to 1965, she lived with musician Bob Zagury.[113] While filming Shalako, she rejected Sean Connery's advances; she said, "It didn't last long because I wasn't a James Bond girl! I have never succumbed to his charm!"[114] In 1967, while married to Sachs, she had a relationship with singer-songwriter Serge Gainsbourg; they recorded two songs together: "Je t'aime... moi non plus", which was not released until 1986, and "Bonnie and Clyde".[115] In 1968, she began dating Patrick Gilles, who co-starred with her in The Bear and the Doll (1970); but she ended their relationship in 1971.[113]

Over the next few years, Bardot dated bartender/ski instructor Christian Kalt, nightclub owner Luigi "Gigi" Rizzi, writer John Gilmore, actor Warren Beatty, and Laurent Vergez, her co-star in Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman.[113][116] In 1975, she entered a relationship with artist Miroslav Brozek and posed for some of his sculptures. Brozek was also an occasional actor; his stage name is Jean Blaise.[117] The couple lived together for four years, separating in December 1979.[118] From 1980 to 1985, Bardot had a live-in relationship with French TV producer Allain Bougrain-Dubourg.[118] In 2018, in an interview accorded to Le Journal du Dimanche, she denied rumors of relationships with Johnny Hallyday, Jimi Hendrix, and Mick Jagger.[102]

Wealth

Yahoo estimated Bardot's net worth to be around US$65 million.[119] She was estimated to have made about $5 million from her 1997 memoir Initials B.B.[106] After her separation from Vadim, Bardot acquired a historic property dating from the 16th century, called Le Castelet, in Cannes. The fourteen-bedroom villa, surrounded by lush gardens, olive trees, and vineyards, consisted of several buildings. She listed it for sale in 2020, for €6 million.[120] In 1958, she bought a second property called La Madrague, located in Saint-Tropez, for 24 million francs, where she lived until her death in 2025.[121][122]

Politics and legal issues

Bardot expressed support for President Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s.[97][123]

In 1997, Bardot and her publisher, Éditions Grasset, were ordered to pay £28,000 because of "hurtful remarks" in her autobiography about her former husband Jacques Charrier and their son who had originally sued for more than £1 million in damages.[106]

In her 1999 book Le Carré de Pluton (Pluto's Square), Bardot criticized the procedure used in the ritual slaughter of sheep during the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha. Additionally, in a section in the book entitled "Open Letter to My Lost France", she writes that "my country, France, my homeland, my land" was "again invaded by an overpopulation of foreigners, especially Muslims". She was fined €1,500 (equivalent to €3,000 in 2023) in 1997 for the original publication of this open letter in Le Figaro,[124] fined €2,785 (equivalent to €5,000 in 2023) in 1998 for making similar remarks,[125][126] and fined €4,500 in June 2000 (equivalent to €7,000 in 2023).[43]

In her 2003 book, Un cri dans le silence (A Scream in the Silence), Bardot contrasted her close gay friends with homosexuals who "jiggle their bottoms, put their little fingers in the air and with their little castrato voices moan about what those ghastly heteros put them through", and said some contemporary homosexuals behave like "fairground freaks".[127] In her defence, Bardot wrote in a letter to a French gay magazine: "Apart from my husband—who maybe will cross over one day as well—I am entirely surrounded by homos. For years, they have been my support, my friends, my adopted children, my confidants."[128][129]

In the same book, Bardot also criticized interracial marriage, immigration, the role of women in politics, and Islam. The book contained a section attacking what she called the mixing of genes, and praised previous generations which, she said, had given their lives to push out invaders.[130] On 10 June 2004, Bardot was convicted for a fourth time by a French court for inciting racial hatred and fined €5,000 (equivalent to €7,000 in 2023).[131] Bardot denied the racial hatred charge and apologized in court, saying: "I never knowingly wanted to hurt anybody. It is not in my character."[132]

In 2008, Bardot was convicted of inciting racial/religious hatred regarding a letter she wrote, a copy of which she sent to Nicolas Sarkozy when he was minister of the interior. The letter stated her objections to Muslims in France ritually slaughtering sheep by slitting their throats without anesthetizing them first. She also said, in reference to Muslims, that she was "fed up with being under the thumb of this population which is destroying us, destroying our country and imposing its habits". The trial concluded on 3 June 2008, resulting in a conviction and a fine of €15,000 (equivalent to €20,000 in 2023).[133] The prosecutor stated she was weary of charging Bardot with offences related to racial hatred.[129]

During the 2008 United States presidential election, Bardot branded Republican Party vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin as "stupid" and a "disgrace to women". She criticized the former Alaskan governor for her stance on global warming and gun control. She was further offended by Palin's support for Arctic oil exploration and by her lack of consideration in protecting polar bears.[134] On 13 August 2010, Bardot criticised American filmmaker Kyle Newman for his plan to produce a biographical film about her. She told him, "Wait until I'm dead before you make a movie about my life!", otherwise "sparks will fly".[135]

In 2014, Bardot wrote an open letter demanding the ban in France of Jewish ritual slaughter shechita. In response, the European Jewish Congress released a statement saying "Bardot has once again shown her clear insensitivity for minority groups with the substance and style of her letter [...] She may well be concerned for the welfare of animals but her longstanding support for the far-right and for discrimination against minorities in France shows a constant disdain for human rights instead."[136] In 2015, Bardot threatened to sue a Saint-Tropez boutique for selling items featuring her face.[137] In 2018, she expressed support for the yellow vests protests.[138]

In the wake of the MeToo movement (adopted in France as #BalanceTonPorc, or "Squeal on your pig") Bardot called actresses claiming to have been victims of sexual harassment "hypocrital, ridiculous, uninteresting" in an interview with Paris Match. She went on to say that "Many actresses flirt with producers to get a role. Then when they tell the story afterwards, they say they have been harassed [...] in fact, rather than benefit them, it only harms them."[139]

On 19 March 2019, Bardot issued an open letter to Réunion prefect Amaury de Saint-Quentin in which she accused inhabitants of the Indian Ocean situated French overseas territory of animal cruelty and referred to them as "autochtones who have kept the genes of savages". In her letter relating to animal abuse and sent through her foundation, she mentioned the "beheadings of goats and billy goats" during festivals, and associated these practices with "reminiscences of cannibalism from past centuries". The public prosecutor filed a lawsuit the following day.[140]

In June 2021, Bardot was fined €5,000 (equivalent to €6,000 in 2023) by the Arras court for public insults against hunters and the president of the Fédération nationale des chasseurs (National Federation of Hunters) Willy Schraen. She had published a post at the end of 2019 on her foundation's website, calling hunters "sub-men" and "drunkards" and carriers of "genes of cruel barbarism inherited from our primitive ancestors", and which specifically insulted Schraen. At the time of the hearing, she had not removed the comments from the website.[141] Following her letter sent to the prefect of Réunion in 2019, she was convicted on 4 November 2021 by a French court for public insults and fined €20,000 (equivalent to €23,000 in 2023), the largest of her fines.[142]

Bardot's last husband Bernard d'Ormale was at some point an adviser to Jean-Marie Le Pen, former leader of National Front (which became National Rally), the main far-right party in France.[45][123] Bardot expressed support for Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Front (National Rally), calling her "the Joan of Arc of the 21st century".[143] She endorsed Le Pen in the 2012 and 2017 French presidential elections.[144][145]

Until her final days, Bardot remained involved in the work of her foundation.[146] She continued to take public positions on animal‑welfare issues, including calling for the abolition of stag hunting.[146]

In her final statements, she acknowledged the deaths of Alain Delon, her long‑time friend and former co‑star, who died in August 2024 aged 88,[146] and Jacques Charrier, her former husband and the father of her son, who died in September 2025.[146]

Health

In early 1958, her breakup with Jean-Louis Trintignant was followed by a reported nervous breakdown in Italy, according to newspaper reports. Press reports also noted a possible suicide attempt with sleeping pills two days earlier, a claim that was denied by her public relations manager.[147] She recovered within several weeks.[97]

According to contemporary press reports, on 28 September 1983, her 49th birthday, Bardot ingested a quantity of sleeping tablets or tranquilizers with red wine at her St. Tropez home and then went to the nearby beach, where she was later found in the water and brought ashore.[118] She was taken to the L'Oasis clinic, where her stomach was pumped, and she was discharged later that evening.[118]

In 1984, Bardot was diagnosed with breast cancer.[B] She declined chemotherapy and opted instead for radiation therapy. She recovered in 1986.[150][151]

On 16 October 2025, it was reported that Bardot had been admitted to the Saint-Jean Hospital in Toulon three weeks earlier for surgery for a "serious illness". The operation was successful, and she was reported to be recovering at her home in Saint-Tropez.[152][153][154]

Death and tributes

Bardot died from cancer at her home, "La Madrague", in Saint-Tropez, on 28 December 2025. She was 91.[155][156]

French president Emmanuel Macron paid tribute to Bardot on social media, describing her as a "legend of the century".[157] The Société Protectrice des Animaux, France's oldest animal‑protection organization, also paid tribute to Bardot, describing her as an "iconic and passionate figure for the animal cause".[158][159]

Legacy

The Guardian named Bardot "one of the most iconic faces, models, and actors of the 1950s and 1960s". She had been called a "style icon" and a "muse for Dior, Balmain, and Pierre Cardin".[161] In fashion, the Bardot neckline (a wide-open neck that exposes both shoulders) is named after her. Bardot popularised this style, which is especially used for knitted sweaters or jumpers, although it is also used for other tops and dresses. Bardot popularized the bikini in her early films such as Manina (1952) (released in France as Manina, la fille sans voiles). The following year, she was also photographed in a bikini on every beach in southern France during the Cannes Film Festival.[162]

Bardot gained additional attention when she filmed ...And God Created Woman (1956) with Jean-Louis Trintignant (released in France as Et Dieu… créa la femme). In it, Bardot portrays an immoral teenager who seduces men in a respectable small-town setting. The film was an international success.[45] Bardot's image was linked to the shoemaker Repetto, who created a pair of ballerinas for her in 1956.[163]

In the 1950s, the bikini was relatively well accepted in France but still considered risqué in the United States. As late as 1959, Anne Cole, one of the United States' largest swimsuit designers, said, "It's nothing more than a G-string. It's at the razor's edge of decency."[164] She also brought into fashion the choucroute (lit. 'sauerkraut') hairstyle (similar to the beehive hair style) and gingham clothes after wearing a checkered pink dress, designed by Jacques Esterel, at her wedding to Charrier.[165] French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir described Bardot as "a locomotive of women's history".[79]

Isabella Biedenharn of Elle wrote that Bardot "has inspired thousands (millions?) of women to tease their hair or try out winged eyeliner over the past few decades". A well-known evocative pose describes an iconic modeling portrait shot around 1960, in which Bardot is dressed only in a pair of black pantyhose, cross-legged over her front and cross-armed over her breasts; known as the "Bardot Pose".[166] This pose has been emulated numerous times by models and celebrities such as Gisele Bündchen,[167] Lindsay Lohan,[168] Elle Macpherson,[169] and Rihanna.[170]

In the late 1960s, Bardot's silhouette was used as a model for designing and modeling the statue's bust of Marianne, a symbol of the French Republic.[59] In addition to popularizing the bikini swimming suit, Bardot was credited with popularising the city of St. Tropez and the town of Armação dos Búzios in Brazil, which she visited in 1964 with her boyfriend at the time, Brazilian musician Bob Zagury.[171] The town hosts a Bardot statue by Christina Motta.[172]

Bardot was idolized by the young John Lennon and Paul McCartney.[173][174] They made plans to shoot a film featuring The Beatles and Bardot, similar to A Hard Day's Night, but the plans were never fulfilled.[45] Lennon's first wife, Cynthia Powell, lightened her hair color to more closely resemble Bardot, while George Harrison made comparisons between Bardot and his first wife, Pattie Boyd, as Cynthia wrote later in A Twist of Lennon. Lennon and Bardot met in person once, in 1968 at the May Fair Hotel, introduced by Beatles press agent Derek Taylor; a nervous Lennon took Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) before arriving, and neither star impressed the other. Lennon recalled in a memoir: "I was on acid, and she was on her way out."[175]

According to the liner notes of his first (self-titled) album, musician Bob Dylan dedicated the first song he ever wrote to Bardot. He also mentioned her by name in "I Shall Be Free", which appeared on his second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. The first-ever official exhibition spotlighting Bardot's influence and legacy opened in Boulogne-Billancourt on 29 September 2009 – a day after her 75th birthday.[176]

Bardot was the subject of eight Andy Warhol paintings in 1974.[177] The Australian pop group Bardot was named after her. Kylie Minogue adopted the Bardot "sex kitten look" on the cover of her album Body Language, released in 2003.[178] In addition to Minogue, women who emulated and were inspired by Bardot include Isabelle Adjani, Emmanuelle Béart, Louise Bourgoin, Zahia Dehar, Faith Hill, Paris Hilton, Georgia May Jagger, Scarlett Johansson, Diane Kruger, Kate Moss, Claudia Schiffer, Elke Sommer, Lara Stone, and Amy Winehouse. Bardot said: "None have my personality." Laetitia Casta embodied Bardot in the 2010 French drama film Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life by Joann Sfar.[179] In 2011, Los Angeles Times Magazine's list of "50 Most Beautiful Women in Film" ranked her number two.[180]

A portrait of Bardot by Warhol, commissioned by Sachs in 1974, was sold at Sotheby's in London on 22 and 23 May 2012. The painting, estimated at £4 million, was part of Sachs' art collection put on sale a year after his death.[181] She inspired Nicole Kidman, who had "Bardot-esque" hair in the 2013 campaign by the British brand Jimmy Choo.[182] In 2015, Bardot was ranked number six in "The Top Ten Most Beautiful Women of All Time" according to a survey carried out by Amway's beauty company in the UK involving 2,000 women.[183]

American alternative rock band Brigitte Calls Me Baby was named after her, inspired by pen-pal correspondence between frontman Wes Leavins and Bardot.[184] Bardot is mentioned in Billy Joel's song "We Didn't Start the Fire," released in 1989. In 2020, Vogue named Bardot number one of "The most beautiful French actresses of all time".[185] In a retrospective retracing women throughout the history of cinema, she was listed among "the most accomplished, talented and beautiful actresses of all time" by Glamour.[186]

The French drama television series Bardot was broadcast on France 2 in 2023. It stars Julia de Nunez and is about Bardot's career from her first casting at age 15 and until the filming of La Vérité ten years later.[187] In 2023, she was mentioned in Olivia Rodrigo's song "Lacy" from her album Guts,[188] and Chappell Roan's "Red Wine Supernova" from her album The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess.[189]

On 12 May 2025, the 90-year-old Bardot was interviewed at her house in Saint-Tropez for 47 minutes. The interview was broadcast on the French network BFMTV and was her first television appearance in eleven years. During the interview she discussed her acting career, songs, love of nature, life memories, and her good health, again expressing her commitment to animal rights. She also said, "Feminism isn't my thing. I like guys," regarding her criticism of feminism and feminist organizations that she had called "excessive or ideological", and expressed her views on the legal problems of Nicolas Bedos and Gérard Depardieu, saying: "Those who have talent and put their hands on a girl's buttocks are relegated to the bottomless pit. We could at least let them continue to live. They can no longer live."[190] She also revealed that she did not use a mobile phone or computer.[191][192][193][194]

Discography

Studio albums

| Year | Original title | Translation | Songwriters(s) | Label | Main tracks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Et dieu... créa la femme (music from Roger Vadim's motion picture) | "And God Created Woman" | Paul Misraki | Versailles | [citation needed] | |

| 1963 | Brigitte Bardot Sings | Serge Gainsbourg Claude Bolling Jean-Max Rivière Fernand Bonifay Spencer Williams Gérard Bourgeois | Philips | "L'appareil à sous" "Invitango" "Les amis de la musique" "La Madrague" "El Cuchipe" | [195] | |

| 1964 | B.B. | André Popp Jean-Michel Rivat Jean-Max Rivière Fernand Bonifay Gérard Bourgeois | "Moi je joue" "Une histoire de plage" "Maria Ninguém" "Je danse donc je suis" "Ciel de lit" | [196] | ||

| 1968 | Bonnie and Clyde (with Serge Gainsbourg) | Serge Gainsbourg Alain Goraguer Spencer Williams Jean-Max Rivière | Fontana | "Bonnie and Clyde" "Bubble Gum" "Comic Strip" | [197] | |

| Show | Serge Gainsbourg Francis Lai Jean-Max Rivière | AZ | "Harley Davidson" "Ay Que Viva La Sangria" "Contact" | [198] |

Other notable singles

| Year | Original Title | Translation | Songwriters(s) | Label | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | "Sidonie" (music from Louis Malle's the motion picture Vie Privée) | Fiorenzo Capri Charles Cros Jean-Max Rivière | Barclay | [199] | |

| 1965 | "Viva Maria!" (music from Louis Malle's eponymous motion picture) (with Jeanne Moreau) | Jean-Claude Carrière Georges Delerue | Philips | [199] | |

| 1966 | "Le soleil" | "The Sun" | Jean-Max Rivière Gérard Bourgeois | AZ | [200] |

| 1969 | "La fille de paille" | "The Straw Girl" | Franck Gérald Gérard Lenorman | Philips | [201] |

| 1970 | "Tu veux ou tu veux pas" "(Nem Vem Que Nao Tem)" | "Do You Want or Not" | Pierre Cour Carlos Imperial | Barclay | [202] |

| "Nue au soleil" | "Naked Under the Sun" | Jean Fredenucci Jean Schmidtt | [203] | ||

| 1972 | "Tu es venu mon amour" / "Vous Ma Lady" (with Laurent Vergez) | "You Came My Love" / "You My Lady" | Hugues Aufray Eddy Marnay Eddie Barclay | [citation needed] | |

| "Boulevard du rhum" (with Guy Marchand) (music from Robert Enrico's motion picture) | "Boulevard of Rhum" | François De Roubaix Jean-Paul-Egide Martini | [citation needed] | ||

| 1973 | "Soleil de ma vie" (with Sacha Distel) | "Sun of My Life" | Stevie Wonder Jean Broussolle | Pathé | [204] |

| 1982 | "Toutes les bêtes sont à aimer" | "All Animals Must Be Loved" | Jean-Max Rivière | Polydor | [205] |

| 1986 | "Je t'aime... moi non plus" (with Serge Gainsbourg) (recorded but shelved in 1968) | "I Love You... Me Neither" | Serge Gainsbourg | Philips | [206] |

Books written

- Noonoah: Le petit phoque blanc (Grasset, 1978)[207]

- Initiales B.B. (autobiography, Grasset & Fasquelle, 1996)[208]

- Le Carré de Pluton (Grasset & Fasquelle, 1999)[209]

- Un Cri dans le silence (Éditions du Rocher, 2003)[210]

- Pourquoi? (Éditions du Rocher, 2006)[211]

Accolades

Awards and nominations

- 12th Victoires du cinéma français (1957): Best Actress, win, as Juliette Hardy in And God Created Woman.[212]

- 11th Bambi Awards (1958): Best Actress, nomination, as Juliette Hardy in And God Created Woman.[213]

- 14th Victoires du cinéma français (1959): Best Actress, win, as Yvette Maudet in In Case of Adversity.[214]

- Brussels European Awards (1960): Best Actress, win, as Dominique Marceau in The Truth.[215]

- 5th David di Donatello Awards (1961): Best Foreign Actress, win, as Dominique Marceau in The Truth.[63]

- 12th Étoiles de cristal (1966): Best Actress, win, as Marie Fitzgerald O'Malley in Viva Maria!.[216]

- 18th Bambi Awards (1967): Bambi Award of Popularity, win.[217]

- 20th BAFTA Awards (1967): BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress, nomination, as Marie Fitzgerald O'Malley in Viva Maria!.[218]

Honours

- 1980: Medal of the City of Trieste.[219]

- 1985: Legion of Honour.[C][221] Medal of the City of Lille.[219]

- 1989: Peace Prize in humanitarian merit.[219]

- 1992: Induction into the United Nations Environment Programme's Global 500 Roll of Honour.[222] Creation in Hollywood of the Brigitte Bardot International Award as part of the Genesis Awards.[223]

- 1994: Medal of the City of Paris.[224]

- 1995: Medal of the City of Saint-Tropez.[225]

- 1996: Medal of the City of La Baule.[219]

- 1997: Greece's UNESCO Ecology Award. Medal of the City of Athens.[219]

- 1999: Asteroid 17062 Bardot was named after her.[226]

- 2001: PETA Humanitarian Award.[163]

- 2008: Spanish Altarriba foundation Award.[227]

- 2017: A statue of 700 kilograms (1,500 lb) and 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) high was erected in her honor in central Saint-Tropez.[228]

- 2019: GAIA Lifetime Achievement Award from the Belgian association for the defense of animal rights.[229]

- 2021: Her effigy in Saint-Tropez was dressed in 1400 gold leaves of 23.75 carats each.[230]

See also

- "Brigitte Bardot", a song named after her

- List of animal rights advocates

- List of barefooters

Notes

- Original quote: "Si cette petite doit devenir putain ou pas, ce ne sera pas le cinéma qui en sera la cause."[34]

- Bardot admits to two abortions in her memoir and is the first openly postabortive celebrity to go public with a breast cancer diagnosis, followed by Gloria Steinem and Sondra Locke.[148] Scientific research studies have not found a causal relationship.[149]

- Although it was awarded to her, Bardot refused to attend, as did Catherine Deneuve and Claudia Cardinale.[220]

References

- "And Bardot Became BB". Institut français du Royaume-Uni. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Probst 2012, p. 7.

- Cherry 2016, p. 134; Vincendeau 1992, p. 73–76.

- Wypijewski, Joann (30 March 2011). "Elizabeth Taylor: What Becomes a Legend Most". The Nation. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Handley, John (16 March 1986). "St. Tropez: What Hath Brigitte Bardot Wrought?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 11 October 2005.

- Poirier, Agnès (21 September 2009). "Happy birthday, Brigitte Bardot". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Brigitte Bardot's 30 years of sympathy for the far right". Le Monde. 28 December 2025. Retrieved 30 December 2025.

- Ganley, -Elaine; Ganley, Associated Press Elaine; Press, Associated (28 December 2025). "Brigitte Bardot, 1960s French sex symbol turned militant animal rights activist, dies at 91". PBS News. Retrieved 30 December 2025.

- Vanderhoof, Erin (5 November 2021). "Brigitte Bardot is Handed Her Sixth Fine for 'Inciting Racial Hatred'". Vanity Fair.

- Poirier, Agnès (20 September 2014). "Brigitte Bardot at 80: still outrageous, outspoken and controversial". The Guardian.

- Bardot 1996, p. 15.

- "Brigitte Bardot: 'J'en ai les larmes aux yeux'". Le Républicain Lorrain (in French). 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- Singer 2006, p. 6.

- Bigot 2014, p. 12.

- Bigot 2014, p. 11.

- Lelièvre 2012, p. 18.

- Bardot 1996, p. 45.

- Duncan, Michelle (30 September 2025). "Brigitte Bardot at Home: 15 Photos of the French Icon's Offscreen Life Through the Decades". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- Poirier, Agnès (20 September 2014). "Brigitte Bardot at 80: still outrageous, outspoken and controversial". The Observer. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Singer 2006, p. 10.

- Bardot 1996, p. 45; Singer 2006, p. 10–14.

- Singer 2006, p. 10–12.

- Singer 2006, p. 10–11.

- "chalet Bardot". Amis du Domaine de Marly (in French). Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- "Brigitte Bardot marries Jacques Charrier". British Pathé. Louveciennes, France. Archived from the original on 3 January 2026. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

From the Riviera they sped to Louveciennes for the civil wedding by the local mayor and the reception at home.

170178.mp4 - Singer 2006, p. 11–12.

- Singer 2006, p. 12.

- Singer 2006, p. 11.

- Caron 2009, p. 62.

- Pigozzi, Caroline. "Bardot s'en va toujours en guerre... pour les animaux". Paris Match. No. January 2018. pp. 76–83.

- Bardot 1996, p. 67.

- Singer 2006, p. 19.

- "Paris". Variety. 21 February 1951. p. 62.

- Bardot 1996, p. 68–69.

- Bardot 1996, p. 69.

- Bardot 1996, p. 70.

- Bardot 1996, p. 72.

- Bardot 1996, p. 73; Singer 2006, p. 22.

- "Brigitte Bardot at Louveciennes". Getty Images. 29 April 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- "Brigitte Bardot poses in October 1951". Getty Images. 26 June 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- "Brigitte Bardot's Life in Photos". ELLE. 28 December 2025. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- Bardot 1996, p. 81.

- Edvinsson, Rodney. "Historical Currency Converter". Historicalstatistics.org.

- Bardot 1996, p. 84.

- Robinson, Jeffrey (1994). Bardot — Two Lives (First British ed.). London: Simon & Schuster. ASIN: B000KK1LBM.

- "The Dam Busters". The Times. London. 29 December 1955. p. 12.

- Servat. p. 76.

- Box office figures in France for 1956 at Box Office Story

- Vagg, Stephen (29 December 2025). "Brigitte Bardot: Ten Films Worth Watching". Filmink. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- Most Popular Film of the Year. The Times (London, England), Thursday, 12 December 1957; pg. 3; Issue 54022.

- Lev, Peter (1993). The Euro-American Cinema. University of Texas Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-292-76378-4.

- "France's Brigitte Bardot". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2026.

- "Mam'selle Kitten New box-office beauty". Australian Women's Weekly. 5 December 1956. p. 32. Retrieved 5 March 2019 – via Trove.

- "Brigitte Bardot: her life and times so far – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Brigitte Bardot: Rare and Classic Photos of the Original 'Sex Kitten'". Time. April 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- The earliest use cited in the OED Online (accessed 26 November 2011) is in the Daily Sketch, 2 June 1958.

- O'Neil, Paul (1958). "Critics To The Contrary, B. B.'S Appeal Is Not Limited To Her Body". p. 57.

- "Box office information for Love is My Profession". Box office story.

- Bricard, Manon (12 October 2020). "La naissance d'un sex symbol" [The birth of a sex symbol]. L'Internaute (in French). Archived from the original on 4 December 2021.

- "Paris". Variety. 22 August 1956. p. 62.

- "1959 French box office". Box Office Story. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "Box office figures in France for 1956". Box Office Story (in French).

- Roberts, Paul G (2015). "Brigitte Bardot". Style icons Vol 3 − Bombshells. Sydney: Fashion Industry Broadcast. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-6277-6189-5.

- Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 281.

- Vagg, Stephen (11 August 2025). "Forgotten British Film Studios: The Rank Organisation, 1965 to 1967". Filmink. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- "ABC's 5 Years of Film Production Profits & Losses", Variety, 31 May 1973 p. 3.

- "Bardot revived as download star". BBC News. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- "Bardot, Deneuve, Casta... Elles ont incarné Marianne avant (peut-être) Simone Veil". SudOuest.fr (in French). 13 February 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- "Ces femmes qui ont prêté leurs traits à Marianne". www.rtl.fr (in French). 18 July 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- Wilson, Timothy (7 April 1973). "Timothy Wilson meets Roger Vadim". The Guardian. London (UK). p. 9.

- Morgan, Gwen (4 March 1973). "Brigitte Bardot: No longer a sex symbol". Chicago Tribune. p. d3.

- "Brigitte Bardot Gives Up Films at Age of 39". The Modesto Bee. Modesto, California. UPI. 7 June 1973. p. A-8. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- Thompson, Isobel (28 December 2025). "Brigitte Bardot, French Screen Legend and Style Icon, Dies". Vogue. Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- De Breteuil, Paul (22 October 2024). "Brigitte Bardot appelle à la mobilisation pour la libération de l'activiste écologiste Paul Watson" [Brigitte Bardot calls for rallying for the release of environmental activist Paul Watson]. Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- Cavallaro, Régine (1 January 2009). "Paul Watson, pirate au grand coeur" [Paul Watson, pirate with a big heart]. Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- Marie, Juliette (23 July 2024). "Arrestation de Paul Watson: ce qu'il faut savoir sur le fondateur de Sea Shepherd en 6 dates clés" [Arrest of Paul Watson: what you need to know about the founder of Sea Shepherd in 6 key dates]. Ouest-France (in French). Archived from the original on 23 July 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- "Brigitte Bardot foundation for the welfare and protection of animals". fondationbrigittebardot.fr. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Follain, John (9 April 2006) "Brigitte Bardot profile", The Times Online: Life & Style,. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- Borg, Bertrand (30 June 2017). "'Stop eating horses', Brigitte Bardot tells Maltese". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- "Brigitte Bardot saves doomed horse". United Press International. 22 July 1984. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- "Photoicon Online Features: Andy Martin: Brigitte Bardot". Photoicon.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Mr Pop History". Mr Pop History. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Brozan, Nadine (29 January 1994). "Chronicle". The New York Times. p. 20. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- "Bardot 'saves' Bucharest's dogs". BBC News. 2 March 2001. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Brigitte Bardot pleads to Denmark in dolphin 'slaughter', AFP, 19 August 2010.

- Victoria Ward, Devorah Lauter (4 January 2013). "Brigitte Bardot's sick elephants add to circus over French wealth tax protests", telegraph.co.uk; accessed 4 August 2015.

- "Sea Shepherd Conservation Society". Seashepherd.org. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- Bardot commits to animal welfare in Bodhgaya Archived 19 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, phayul.com; accessed 4 August 2015.

- "Bardot condemns Australia's plan to cull 2 million feral cats". ABC News. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- "Manifestations en France contre l'extradition du militant écologiste Paul Watson au Japon" [Protests in France against the extradition of environmental activist Paul Watson to Japan]. Libération (in French). Agence France-Presse. 11 August 2024. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- Sundresses, bikinis, headbands and ballet flats: Brigitte Bardot's legacy also in style

- Brigitte Bardot, icon of French cinema, dies at 91

- Némard, Perrine (19 November 2020). "Brigitte Bardot évoque ses nombreuses conquêtes : "C'est moi qui choisissais"" [Brigitte Bardot talks about her many conquests: 'I was the one who chose']. Paris Match (in French). Archived from the original on 28 November 2021 – via Orange S.A.

- Arlin, Marc (1 February 2018) [modified 8 June 2023]. "Brigitte Bardot : infidèle, elle dévoile la raison de ses multiples adultères" [Brigitte Bardot: unfaithful, she reveals the reason for her multiple adulteries]. Télé-Loisirs (in French). Archived from the original on 28 November 2021.

- "Brigitte Bardot and Roger Vadim standing at the altar during their wedding ceremony". Getty Images. Paris. 12 December 1952. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- Neuhoff, Éric (12 August 2013). "Brigitte Bardot et Roger Vadim – Le loup et la biche". Le Figaro (in French). p. 18.

- Bardot 1996

- Paris Match (18 June 1959). "Before the Wedding Of Brigitte Bardot And Jacques Charrier". Getty Images. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- Paris Match (18 June 1959). "After the Wedding Of Brigitte Bardot And Jacques Charrier". Getty Images. Louveciennes. Retrieved 3 January 2026.

- "A Ford fiesta". Los Angeles Times. 11 April 2011.

- Sanwari, Ahad (28 September 2024). "Brigitte Bardot's complicated love life at 90: from her Hollywood affairs to her four marriages". Hello!. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- "Brigitte Bardot : Elle règle ses comptes !" [Brigitte Bardot: She settles her accounts!]. France Dimanche (in French). 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021.

- "Brigitte Bardot bereut verletzende Aussagen über ihren Sohn". Schweizer Illustrierte (in Swiss High German). Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- Димков, Јасмина Кантарџиева (27 January 2020). "She called her child a tumor and refused to breastfeed: What happened to Brigitte Bardot's son?". slobodenpecat.mk. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- Tremaine, Julie (20 July 2023). "Brigitte Bardot's Dating History: From Roger Vadim to Bernard d'Ormale". People. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- Lichfield, John (7 March 1997). "Bardot in the doghouse for wishing her son was a puppy". The Independent. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- "Nicolas-Jacques Charrier : l'enfant du scandale devenu père de famille discret". Marie Claire (in French). 18 January 2025. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- Cardinal, Léa (11 January 2025). "Brigitte Bardot : à quoi ressemble la vie de son fils, Nicolas Charrier, aujourd'hui ?". Gala (in French). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- "Gunter Sachs". The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- https://www.mensjournal.com/entertainment/brigitte-bardot-husband-bernard-d-ormale-vadim-gunter-sachs-married-husbands

- Goodman, Mark (30 November 1992). "A Bardot Mystery". People. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Sacha Distel". The Independent. 23 July 2004. Retrieved 4 December 2025.

- Singer, B. (2006). Brigitte Bardot: A Biography. McFarland, Incorporated Publishers. ISBN 9780786484263. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Tizio, Alexandra (1 November 2020). "Flashback ..." [Flashback: when Brigitte Bardot refused the advances of Sean Connery]. Gala (in French). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021.

- Gorman, Francine (28 February 2011). "Serge Gainsbourg's 20 most scandalous moments". The Guardian.

- Malossi, G. (1996). Latin Lover: The Passionate South. Charta. ISBN 9788881580491. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Brigitte Bardot and sculptor Miroslav Brozek at La Madrague in St.-Tropez. June 1975, Getty Images

- Carlson, Peter (24 October 1983). "Swept Away by Her Sadness". People. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Brigitte Bardot – News, Photos, Videos, Movies or Albums | Yahoo". uk.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- R.P. (7 July 2020). "La sublime villa cannoise de Brigitte Bardot est à vendre (photos)" [Brigitte Bardot's sublime Cannes villa is for sale [photos]]. Paris Match (in French). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021.

- "Brigitte Bardot, the woman who spoke to the sea: farewell to the lady of La Madrague". Paris Select Book. 28 December 2025.

- Blake, Kristin (4 November 2024). "Brigitte Bardot-Inspired Guide to Saint Tropez". French Side Travel. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- Riding, Alan (30 March 1994). "Drinking champagne with: Brigitte Bardot; And God Created An Animal Lover". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Archives, L. A. Times (10 October 1997). "Bardot Is Fined for Inciting Race Hatred". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 January 2026.

- "Showing Her Claws". The Irish Times. 4 February 1998. Retrieved 1 January 2026.

- "Bardot anti-Muslim comments draw fire". BBC News. London. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Webster, Paul; Hearst, David (5 May 2003). "Anti-gay, anti-Islam Bardot to be sued". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- Usborne, David (24 March 2006). "Brigitte a Political Animal". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- "Bardot fine for stoking race hate". BBC News. London, UK. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- "Bardot fined for 'race hate' book". BBC News. 10 June 2004. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Larent, Shermy (12 May 2003). "Brigitte Bardot unleashes colourful diatribe against Muslims and modern France". Indybay. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Bardot denies 'race hate' charge". BBC News. 7 May 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- "Ex-film star Bardot gets fifth racism conviction". Reuters. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Brigitte Bardot calls Sarah Palin a 'disgrace to women'" The Telegraph. 8 October 2008.

- "Brigitte Bardot: 'Wait Until I'M Dead Before You Make Biopic'". Showbiz Spy. 14 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- "EJC outraged at Brigitte Bardot's demand for French government to ban Shechita". Official Site of the European Jewish Congress. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Samuel, Henry (9 June 2015). "Brigitte Bardot declares war on commercial 'abuse' of her image". The Daily Telegraph.

- Fourny, Marc (3 December 2018). "Brigitte Bardot demande "une prime de Noël" pour les Gilets jaunes". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Pulver, Andrew (18 January 2018). "Brigitte Bardot: Sexual harassment protesters are 'hypocritical' and 'ridiculous'". The Guardian.

- "La justice ..." [Justice being seized after offensive remarks by Brigitte Bardot against Reunionese]. Le Monde (in French). AFP, Reuters. 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021.

- Mesureur, Claire (29 June 2021). "Brigitte ..." [Brigitte Bardot convicted for public insult against Willy Schraen, the president of the hunters]. France Bleu (in French). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021.

- "France ..." [France: Brigitte Bardot is fined 20,000 euros for insulting the Reunionese]. Le Monde (in French). AFP, Reuters. 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021.

- Chazan, David (22 August 2014). "Brigitte Bardot calls Marine Le Pen 'modern Joan of Arc". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Willsher, Kim (13 September 2012). "Brigitte Bardot: celebrity crushed me". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Zoltany, Monika (7 May 2017). "Brigitte Bardot Supports Underdog Marine Le Pen in French Presidential Election, Says Macron Has Cold Eyes". Inquisitr. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Simon, Nathalie (28 December 2025). "Brigitte Bardot, une seconde vie au service de la cause animale". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- "Brigitte Bardot in Italy After Breakdown". Los Angeles Times. 9 February 1958. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Bardot 1996, p. 302.

- "Abortion and Breast Cancer Risk". American Cancer Society.

- "Les célébrités touchées par le cancer du sein" [Celebrities affected by breast cancer]. Gala (in French). n.d. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- Madelmond, Marine (17 January 2018). "Brigitte ..." [Brigitte Bardot: why she refused chemotherapy during her breast cancer?]. Gala (in French). Archived from the original on 28 November 2021.

- Roussel, Amandine (16 October 2025). "État préoccupant, « intervention dans le cadre d'une maladie grave: Brigitte Bardot hospitalisée à Toulon". Nice-Matin (in French). Archived from the original on 16 October 2025. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- "French movie star Brigitte Bardot recovering after brief hospital stay". Reuters. 17 October 2025. Archived from the original on 17 October 2025. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- Ferri, Alessia (17 October 2025). "Brigitte Bardot Is in a "Worrying State" After a 3-Week Hospital Stay". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 17 October 2025. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- "Brigitte Bardot died from cancer, says husband". RTE. 7 January 2026. Retrieved 7 January 2026.

- Rahola-Boyer, Sidonie; Triouleyre, Nicole (28 December 2025). "Un corbillard quitte La Madrague, la villa de la star où elle est décédée ce matin" [A hearse leaves La Madrague, the star's villa where she died this morning.]. Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- "«Son mari était à ses côtés» : les derniers instants de Brigitte Bardot révélés" (in French). Europe 1. 28 December 2025. Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- "Brigitte Bardot, French actress and animal rights activist, dies". BBC News. 28 December 2025. Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- Gates, Anita (28 December 2025). "Brigitte Bardot, French Movie Icon Who Renounced Stardom, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- "Mamie Van Doren: "Talking about Marilyn Monroe is strange. To me, she's a person; to most people, she's an idea"". 2017.

- "Brigitte Bardot: the style icon − in pictures". The Guardian. 1 December 2016. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- "Bikinis: a brief history". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- "Brigitte Bardot". Grazia (in French). n.d. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- Johnson, William Oscar (7 February 1989). "In The Swim". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Style Icon: Brigitte Bardot". Femminastyle.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Biedenharn, Isabella (4 November 2014). "The 20 Best Legs Throughout History". Elle. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Slide 18

- Sabrina B. (28 April 2011). "Gisele Bündchen topless joue les Brigitte Bardot..." [Gisele Bündchen topless plays Brigitte Bardot...]. Puremédias (in French). Archived from the original on 22 November 2021.

- Sweeney, Kathleen (2008). Maiden USA: Girl Icons Come of Age. Atlanta: Peter Lang. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-820-48197-5.

- "Ces stars qui ont posé pour Playboy" [These stars who posed for Playboy]. Gala (in French). Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- "Rihanna on GQ magazine". GQ. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021 – via Fashion Has It.

- "TOemBUZIOS.com". toembuzios.com (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- "BúziosOnline.com". BúziosOnline.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Miles, Barry (1998). Many Years from Now. Vintage–Random House. ISBN 978-0-7493-8658-0. p. 69.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Little, Brown and Company (New York). ISBN 978-1-84513-160-9. pg. 171.

- Lennon, John (1986). Skywriting by Word of Mouth. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-015656-5. p. 24.

- Brigitte Bardot at 75: the exhibition Archived 26 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, connexionfrance.com, September 2009; accessed 4 August 2015.

- Sischy, Ingrid (4 October 2011). "The Bardot Variations". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 10 November 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- "Kylie uses sexy Bardot look for new album". ABC News. Paris. Agence France-Presse. 24 October 2003. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024 – via Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Bigot 2014, p. 26–27.

- Spencer, Kathleen (2011). "L.A Times Magazine Names Their 50 Most Beautiful Women In Film". Momtastic. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021.

- Singh, Anita (13 March 2013). "Gunter Sachs Collection at Sotheby's: sale reveals playboy's enduring passion for Brigitte Bardot". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 November 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- Milligan, Lauren (28 October 2013). "Nicole Kidman Talks Becoming Bardot". Vogue. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- "The Top Ten Most Beautiful Women Of ALL Time". Heart. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- Carter, Daisy (2 August 2024). "Brigitte Calls Me Baby: 'Sure, being famous sounds nice, but how do you achieve permanence?'". DIY. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- Garrigues, Manon (4 June 2020). "The most beautiful French actresses of all time". Vogue. Translated by Stephanie Green. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021.

- Smith, Josh (4 August 2020). "From Marilyn to Margot: the most accomplished, talented and beautiful actresses of all time". Glamour. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021.

- "Bardot : découvrez la première photo de Julia de Nunez en Brigitte Bardot et le casting cinq étoiles de la série de France 2". AlloCiné. 13 June 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Sheffield, Rob (14 September 2023). "Every Olivia Rodrigo Song, Ranked". Rolling Stone Australia. Archived from the original on 10 November 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- Cills, Hazel (25 July 2024). "What is it about Chappell Roan?". NPR. Archived from the original on 6 August 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- Fraiji, Maïssane (May 2025). "'I like guys': Brigitte Bardot, 90, speaks out on feminism". MSN. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- Kourak, Radouan (12 May 2025). "Brigitte Bardot makes her big TV comeback after a ten-year absence". Entrevue.fr. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- "Video: Brigitte Bardot's first interview in 11 years: "I'll tell you everything, but on one condition"". Sloboden Pečat. May 2025. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- Bremner, Charles (12 May 2025). "Brigitte Bardot defends 'talented people who grab a girl's bottom'". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- Scott, Fiona; Dolan, Leah (29 December 2025). "French Girl Chic or right-wing pin-up? The complicated style legacy of Brigitte Bardot". CNN. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- "Album Reviews" (PDF). Billboard. 9 November 1963. p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2025. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- "France" (PDF). Cashbox. Vol. XXV, no. 23. 15 February 1964. p. 52. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2025. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- "The Top 100 Alternative Albums of the 1960s (page 27 of 101)". Spin. 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- "France" (PDF). Cashbox. Vol. XXIX, no. 37. 13 April 1968. p. 68. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2025. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- Vincentelli, Elisabeth (28 December 2025). "An Appraisal: From Sex Appeal to the Far Right, Brigitte Bardot Symbolized a Changing France". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2025. Retrieved 28 December 2025.

- "Le soleil". Spotify. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- "La fille de paille". Spotify. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- "Tu veux ou tu veux pas?". Spotify. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- "Nue au soleil". Spotify. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- "Le soleil de ma vie". Spotify. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- "Toutes les bêtes sont à aimer". Spotify. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- Mazdon, Lucy; Wheatley, Catherine (1 November 2010). Je T'Aime... Moi Non Plus: Franco-British Cinematic Relations. Berghahn Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84545-855-3.

- Bardot, Brigitte (1978). Noonoah le petit phoque blanc. Grasset Jeunesse. ISBN 2246005744.

- Bardot 1996.

- Bardot, Brigitte (1999). Le Carre de Pluton. Grasset & Fasquelle. ISBN 2246595010.

- Bardot, Brigitte (2003). Un cri dans le silence. Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 2268047253.

- Bardot, Brigitte (2006). Pourquoi?. Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 9782268059143.

- Choulant 2019, p. 65.

- Lee, Sophie (28 September 2020). "The 10 Chicest Moments in Brigitte Bardot's Career". L'Officiel. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Choulant 2019, p. 93.

- Choulant 2019, p. 103.

- Choulant 2019, p. 156.

- "Bambi Awards 1967" (PDF). Elke Sommer Online (in German). 21 January 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 December 2021.

- "BAFTA: Film in 1967". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021.

- "Media and Art Advisory Board". Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. n.d. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- "Légion d'Honneur: quelles célébrités l'ont refusée?" [Legion of Honor: which celebrities have refused it?]. La Dépêche du Midi (in French). 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021.

- C. Trott, William (11 April 1985). "Brigitte Bardot accepts the French Legion of Honor medal". United Press International.

- Töpfer, Klaus (n.d.). "1992 Global 500 Laureates". UNEP − The Global 500 Roll of Honour for Environmental Achievement. Yumpu. p. 63.

- Robinson, Jeffrey (2014). Bardot, deux vies (in French). Translated by Jean-paul Mourlon. New York: L'Archipel. p. 252. ISBN 978-2-809-81562-7.

- Bigot 2014, p. 303.

- Bigot 2014, p. 255.

- "Discovered at Anderson Mesa on 1999-04-10 by Loneos. (17062) Bardot − 1999 GR8". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021. Site frequently updated with position information of the Mian Belt object.

- "La Fundación Altarriba ..." 20 minutos (in Spanish). 3 May 2008. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "Saint-Tropez ..." [Saint-Tropez: A statue of Brigitte Bardot installed in front of the gendarmerie]. 20 minutes (in French). AFP. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. [The bronze is inspired by a watercolor by the Italian master of erotic cartoon comic, Milo Manara.]

- "Brigitte..." [Brigitte Bardot awarded by GAIA]. DPG Media (in French). 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021.

- Peté, Rodolphe (27 June 2021). "Désormais ..." [Now covered with thousands of gold leaves, the statue of Brigitte Bardot unveiled in Saint-Tropez]. Nice-Matin (in French). Archived from the original on 5 December 2021.

Other sources

- Bardot, Brigitte (1996). Initiales B.B. : Mémoires (in French). Éditions Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246526018.

- Bigot, Yves (2014). Brigitte Bardot. La femme la plus belle et la plus scandaleuse au monde (in French). Don Quichotte. ISBN 978-2-359490145.

- Caron, Leslie (2009). Thank Heaven. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670021345.

- Cherry, Elizabeth (2016). Culture and Activism: Animal Rights in France and the United States. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317156154.

- Choulant, Dominique (2019). Brigitte Bardot pour toujours [Brigitte Bardot Forever] (in French). Paris: Éditions Lanore. ISBN 978-2-8515-7903-4.

- Lelièvre, Marie-Dominique (2012). Brigitte Bardot – Plein la vue (in French). Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-124624-9.

- Probst, Ernst (2012). Das Sexsymbol der 1950-er Jahre (in German). GRIN Publishing. ISBN 978-3-656186212.